Joyce Carol Oates fights for the underdog. In “Black Water,” she imagines a fictionalized version of Chappaquiddick seen through the eyes of a thinly veiled character drawn to resemble Mary Jo Kopechne, hoping that the Senator would return to rescue her as her life ticks away. In an upcoming post-modern novel, she is re-imagines the friendship between two doomed Hollywood personae, Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Short, as they moved in the some of the same circles. Monroe became a Hollywood icon and died famously in 1962. Short emerged as famous the victim in “The Black Dahlia,” a murder that haunts Los Angeles to this very day.

Joyce Carol Oates fights for the underdog. In “Black Water,” she imagines a fictionalized version of Chappaquiddick seen through the eyes of a thinly veiled character drawn to resemble Mary Jo Kopechne, hoping that the Senator would return to rescue her as her life ticks away. In an upcoming post-modern novel, she is re-imagines the friendship between two doomed Hollywood personae, Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Short, as they moved in the some of the same circles. Monroe became a Hollywood icon and died famously in 1962. Short emerged as famous the victim in “The Black Dahlia,” a murder that haunts Los Angeles to this very day.

In her latest work, she is the underdog we root for as she moves through a difficult chapter of her own life.

The Luncheon Society sat down with Joyce at One Market in San Francisco and The Century Association, thanks to the kind intercession of Enzo Viscusi.

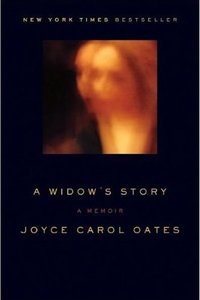

Her output is nothing short of prodigious. At the moment, Joyce Carol Oates has penned 60 novels, 30 collections of short stories, 10 volume of poetry, and all are written by hand. She joined The Luncheon Society in San Francisco and Manhattan to discuss her latest personal and moving book titled, “A Widow’s Story, A Memoir,” which detailed her descent into widowhood.

Her output is nothing short of prodigious. At the moment, Joyce Carol Oates has penned 60 novels, 30 collections of short stories, 10 volume of poetry, and all are written by hand. She joined The Luncheon Society in San Francisco and Manhattan to discuss her latest personal and moving book titled, “A Widow’s Story, A Memoir,” which detailed her descent into widowhood.

“My Husband died, my life collapsed.” As the book jacket notes, “A Widow’s Story illuminates one woman’s struggle to comprehend a life without the partnership that had sustained and defined her for nearly half a century. As never before, Joyce Carol Oates shares the derangement of denial, the anguish of loss, the disorientation of the survivor amid a nightmare of “death-duties,” and the solace of friendship. She writes unflinchingly of the experience of grief—the almost unbearable suspense of the hospital vigil, the treacherous “pools” of memory that surround us, the vocabulary of illness, the absurdities of commercialized forms of mourning. Here is a frank acknowledgment of the widow’s desperation—only gradually yielding to the recognition that this is my life now.” Continue reading